The Crisis in Corporate Criminal Liability

Last week in my White Collar Crime class we discussed corporate criminal liability. The presence of corporations as potential defendants is one of the distinguishing features of white collar crime. The way corporate criminal liability has been trending for the past decade, however, the topic is starting to feel more appropriate for a course in legal history.

Indicting and convicting big corporations has fallen out of favor, increasingly replaced by a system of negotiated Deferred Prosecution Agreements and Non-Prosecution Agreements. It’s a troubling trend and a sign that something in the criminal justice system is out of whack.

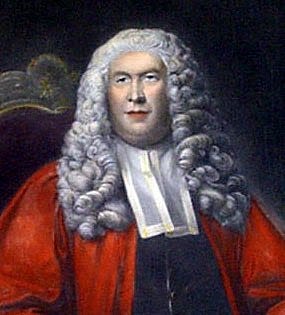

No Soul to be Damned, and No Body to be Kicked

At common law, corporations could not be charged with a crime. With “no soul to be damned, and no body to be kicked,” companies were not considered an appropriate target of criminal sanctions. A corporation could not be deterred from criminal conduct through fear of moral condemnation in this life or the next. Nor could a company be deterred through fear of corporal punishment or be locked up to protect the rest of us. Criminal law as applied to an artificial entity just didn’t seem to make sense.

The Supreme Court tossed this common law rule aside more than 100 years ago in New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Co. v. United States (1909). The railroad and its freight manager were convicted of providing illegal rebates to sugar producers to encourage them to ship their product by rail rather than by water.

The company argued it could not be convicted because to do so would harm innocent shareholders without due process. Shareholders had not been charged and had no opportunity to defend themselves, but they were the ones who would suffer if the company were convicted. The railroad also argued that a criminal act could not truly be considered an act of the corporation unless formally authorized by the board of directors, and the freight manager had been acting on his own.

The Supreme Court rejected both arguments. Adopting the theory of respondeat superior (“let the master answer”) from tort law, the Court concluded the same doctrine applies to criminal liability and makes the corporation liable for the criminal acts of its agents. The Court reasoned that criminal sanctions are essential to controlling corporate misbehavior and that it is appropriate to hold the company responsible for the crimes of those acting on its behalf.

Under respondeat superior, in federal cases a corporation is liable for the criminal acts of its agents if those acts were taken at least in part to benefit the corporation and if the agent was acting within the actual or apparent scope of his or her employment. This is true even if the actions were those of a “rogue employee” acting without authorization.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, corporate criminal liability was an important weapon in the battle against white-collar crime. In the past decade, however, there has been a marked decrease in the Department of Justice’s appetite for prosecuting big corporations. Many people trace this development to the Arthur Andersen debacle.

The Legacy of Arthur Andersen

Arthur Andersen, one of the so-called “big five” accounting firms, was indicted in 2002 for obstruction of justice. Andersen was Enron’s auditor, and a few employees in its Texas office had shredded millions of pages of Enron-related documents in anticipation of an SEC investigation. Andersen was convicted at trial and appealed all the way to the Supreme Court.

In 2005 the Supreme Court reversed the conviction, finding that the jury instructions in the case had been flawed. But it was a hollow victory; during the appeals the company went out of business as clients fled from an accounting firm operating under a criminal cloud. More than 28,000 employees in the U.S., and 85,000 worldwide, lost their jobs.

The Department of Justice was roundly criticized for the Andersen prosecution, which caused tremendous collateral damage to innocent parties based on the actions of a handful of employees. The fallout seemed to make DOJ gun-shy about indicting companies. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, some administration officials even expressed concern that certain companies may be “too big to jail” and should not be prosecuted because if they were to collapse the damage to the economy would be too great.

Deferred Prosecution Agreements and Non-Prosecution Agreements

This growing reluctance to indict and prosecute companies has coincided with another phenomenon: the rise of the Deferred Prosecution Agreement. (Non-Prosecution Agreements are basically the same thing; for simplicity here I will just refer to DPAs.)

A DPA is a negotiated deal to resolve a criminal investigation. In a DPA, the prosecution agrees it will not proceed with criminal charges if the corporation complies with the term of the agreement. Typically these terms include paying fines or restitution, undertaking internal corporate reforms, cooperating in ongoing investigations, and hiring (and paying for) a monitor to oversee the company’s compliance for a period of years. If the company fully complies with the agreement, any potential criminal charges are dropped.

DPAs have seen an explosive rise in popularity. In the early 2000s before the Andersen case, there was an average of only 2 or 3 per year. In recent years the average number of cases resolved through DPAs has been in the thirties. The real number is probably higher because not all such agreements are made public (particularly NPAs).

Both sides find much to like in a DPA. The prosecution obtains many of the same remedies (including substantial fines) that it could obtain from an indictment and conviction, and saves the time and expense of a lengthy grand jury investigation and trial. Avoiding criminal prosecution also avoids the collateral damage (and subsequent criticism) that might result from an Andersen-like collapse of a company. For its part, the corporation avoids the risk of a criminal conviction and potentially crippling penalties. It is able to resolve the investigation and put the matter behind it, providing the certainty that Wall Street craves.

Fearing they could be the next Andersen, executives may jump at the chance to reach an agreement and avoid even a slight possibility of criminal sanctions. But although DPAs are popular and seem like a win-win, I believe their rise is a troubling trend.

The Problems with DPAs

Criminal sanctions are meant to be reserved for the most egregious conduct, in cases in which the government can prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt to a judge or jury. As more and more criminal cases are resolved through DPAs, these principles erode. Prosecutors no longer must assemble a strong enough case to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt to a neutral factfinder; they need only assemble enough evidence to convince the corporation that it should cut a deal to get the matter resolved. This almost certainly results in more marginal cases being pursued.

The discipline of conducting a grand jury investigation and assembling the evidence necessary to prepare for trial has a way of weeding out cases that don’t really merit criminal sanctions or that can’t be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. That discipline is lost if prosecutors can simply pressure a company into a DPA in a borderline case.

A criminal prosecution also contains checks and balances on prosecutorial power. A judge rules on the law, and a judge or jury decides guilt or innocence. If there is a conviction a judge, not the prosecutor, determines the sentence. With a DPA, all of those checks and balances are gone. The prosecutor is also judge and jury, deciding not only that there has been a violation but what the appropriate penalty should be.

This also means the government’s legal theories are seldom tested. In a prosecution, new or aggressive legal interpretations would be evaluated by a judge; with a DPA, the law is whatever the prosecutor says it is. This has been particularly true in areas such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, where so many cases are resolved by DPAs that there is very little decided caselaw. The law comes to be defined through the “common law” development of the prosecution’s interpretations as embodied in the DPAs, with little or no judicial oversight.

All of this places enormous additional power in the hands of prosecutors. It also transforms the criminal justice system into a quasi-regulatory regime, with prosecutors making decisions and demands about appropriate corporate behavior. The DPA may mandate changes in Board membership, internal compliance programs, and other business practices that affect corporate governance. Prosecutors end up shifting their focus from punishing past criminal acts to shaping future corporate behavior. This is not a criminal prosecutor’s area of expertise.

But perhaps the most damaging result of this trend is the erosion of the moral force of the criminal law. Criminal sanctions are a unique deterrent due to the moral condemnation of the community that accompanies them. Individuals do not want to be labeled a criminal in the eyes of the community; it carries a stigma not associated with any other penalty. Most defendants, particularly white-collar defendants (who typically are not career criminals), will work hard to avoid that stigma.

Although corporations have no “soul to be damned,” this same moral stigma still applies to corporate criminal sanctions. One simple reason is the bottom line: companies do not want their customers to see them labeled as a criminal organization. It’s bad for business to be thought of as a crook. What’s more, companies are run by individuals for whom this moral condemnation also holds sway – the CEO of a company does not want her friends and neighbors to see in the news that the company she leads is a criminal. One need only see how mightily a corporation will strive to avoid a criminal conviction to know that this deterrent effect of criminal sanctions is real.

If large companies start to believe that criminal sanctions are basically off the table, the criminal law will lose this unique deterrent capability. Corporations will know that, no matter how bad the misconduct, they can likely buy their way out of a criminal case by entering into a DPA. This may encourage corporate officers to skate closer to the criminal line – or to jump over it.

The Future of Corporate Criminal Prosecutions

It’s hard to see a good solution to this trend. Corporations are under tremendous pressure to cut a deal and avoid prosecution. Resolving an investigation short of criminal sanctions usually will be rewarded by shareholders and the market. And as long as prosecutors know they have this tremendous leverage, their incentive will be to force as many companies as possible into a DPA rather than pursuing a full-blown criminal case.

My friend and former colleague Mike Volkov, who writes the Corruption, Crime and Compliance blog, wrote a great post a few weeks ago called “Corporations Need to Say the Words – ‘Let’s Go to Trial!’” He argues that, in appropriate cases, more companies need to stand up to DOJ and not simply roll over during a criminal investigation. If more corporations resisted the pressure to cut a deal, they might find many of these investigations actually going away or being referred to other agencies for civil enforcement. Call the prosecutors' bluff, and they may decide that a potential criminal case is not really strong enough to merit the investment of the next two years of their lives.

Even when there is an indictment, it most likely will not mean the end of the company. Arthur Andersen was in a unique situation given the nature of its business and the general post-Enron hysteria that was raging at the time. Historically, though, a criminal indictment usually does not result in a corporate “death penalty.” General Electric, Exxon, Tyson Foods, Genentech -- all have been criminally indicted at one time or another and are still going strong.

Companies need to realize that even if they are indicted it will be bad but need not be fatal. If necessary the criminal case may be resolved through a plea agreement with terms probably no more severe than those in a DPA, and with the added benefit that the terms will be reviewed by a judge. Or the case may be taken to trial and defended, with the chance that the company will prevail.

Prosecutors, too, need to recognize that they do not need to be gun-shy about indicting companies based on the Arthur Andersen experience. In appropriate cases, when criminal sanctions against a company truly are called for, criminal charges should be pursued to fulfill the special moral mission of the criminal law.

We already have enough regulatory agencies policing corporate behavior. Prosecutors should get back to indicting and trying criminal cases – and more corporations should develop the backbone to say, “see you in court.”