The Julian Assange Indictment and Freedom of the Press

Last month the Justice Department announced a superseding indictment of Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks, charging him with multiple violations of the Espionage Act for soliciting and disclosing classified materials. The case has raised concerns over whether the government might apply the same prosecution theories to mainstream journalists who obtain and publish classified information.

Although prosecutors are unlikely to go there, the Assange indictment highlights how much we rely on prosecutorial discretion to contain the sweeping and potentially troubling reach of certain criminal statutes. In an age where faith in the sound exercise of that discretion is eroding, prosecutors simply saying “we wouldn’t do that” may cease to be a satisfactory answer.

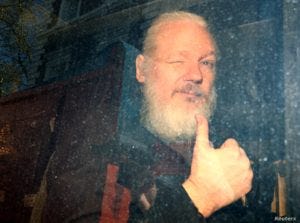

Julian Assange

The Assange Indictment

In 2010 Julian Assange received hundreds of thousands of classified documents from Chelsea Manning, then known as Bradley Manning, who worked as an intelligence analyst for the army. Manning unlawfully sent Assange materials related to the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, as well as thousands of classified State Department cables. Assange released the documents on Wikileaks during 2010 and 2011. It was one of the largest breaches of classified information in U.S. history.

In 2013 Manning was convicted of multiple felonies, including espionage. It appeared Assange would not be prosecuted. But this past April the Justice Department unveiled a sealed indictment charging Assange based on his dealings with Manning. Initially Assange was charged only with conspiracy to violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, for helping Manning try to crack a computer password in order to hack into additional classified files. That effort was unsuccessful, but Assange was charged with conspiracy for taking part in the attempted hacking with Manning.

That initial indictment of Assange generally met with cautious approval from the media because DOJ had not charged him for obtaining or publishing any of the leaked materials. But on May 23, the Justice Department returned a superseding indictment. The new 18-count indictment includes multiple charges that Assange violated the Espionage Act by encouraging Manning to obtain classified information and leak it to Assange. It also charges Assange with three Espionage Act violations for publishing classified materials that revealed the identities of confidential sources who had helped the United States, including Afghans, Iraqis, journalists, human rights advocates, and religious leaders. The government alleges that by publishing that information, Assange knowingly placed those sources in grave danger.

The superseding indictment has caused great concern in the journalism community. National security reporters routinely receive and publish classified information, and may encourage sources to provide them with that information. What would prevent the Justice Department from applying the same legal theories used in the Assange case to prosecute a more mainstream journalist at the Washington Post or New York Times? The answer may be: legally, not much.

The Espionage Act

The Espionage Act, 18 U.S.C. 793, is a World War I-era law that prohibits obtaining or disclosing national security information with the intent or reason to believe it could be used to harm the United States or benefit a foreign nation. Several sections of the statute apply to those who are authorized to have the information but then improperly disclose it to others. These are the sections that may be used to prosecute those who leak classified information to a reporter. Most of the charges against Assange allege that he violated these sections by aiding and abetting or conspiring with Manning to have her leak the information to Assange.

Section 793(e) of the Act applies to those who are not otherwise authorized to have the information but obtain it and then transmit or communicate it to others also not authorized to have it. This is the section that potentially could apply to a journalist who receives a leak of classified information and then publishes it so others can read it. Assange is charged under this section for publishing only the materials that revealed the identities of confidential intelligence sources. He is not charged for publishing any of the hundreds of thousands of other documents he received from Manning and posted on Wikileaks.

The Espionage Act and the Press

Prior to the Assange case, the government had never prosecuted someone who at least claimed to be a journalist for publishing classified information received from a source. But the possible application of the Espionage Act to such a journalist has always been lurking in the background.

The concerns raised by the Assange indictment should be placed in the historical context of battles between the press and the executive branch that began escalating during the Obama Administration. The Obama Justice Department significantly expanded the use of the Espionage Act to prosecute leakers of national security information. You often hear that the Obama administration pursued more leak prosecutions than every prior administration combined. That’s true, but it was still only eight prosecutions, or about one a year. Even this relatively modest pace of cases resulted in blistering attacks from the media, which claimed the administration was engaging in a “war on the press” by trying to silence leakers.

There was arguably a technological rationale for the Obama administration’s change in policy. There have always been leaks of classified information to the press. But in the Watergate era, for example, if a reporter received classified information he or she generally would do some work to verify it. The reporter would also call government officials about the information and request comment. That at least gave officials the opportunity to try to persuade the reporter not to publish the information or to delay publication because it would jeopardize national security. Historically there have been times when the mainstream press honored such requests.

With the rise of the Internet, those safety valves have been largely obliterated. Now there are many websites and individuals who consider themselves journalists who are happy to take leaked information and just throw it up on their website. That’s what Assange did with the materials he received from Manning, as well as with the stolen Democratic emails and documents he received from Russian hackers during the 2016 presidential election. It made some sense for the Obama administration to try to plug serious leaks by cracking down on leakers themselves. In the age of Wikileaks, the only opportunity to prevent potentially damaging information from being immediately released worldwide, to friends and enemies alike, is to prevent it from ever being leaked in the first place.

Risen? Rosen? The Cases of the Two James

Leak prosecutions in the Obama years were brought only against the leakers, not against journalists. But they still caused considerable tension between the administration and the journalism community. For example, prosecutors had a protracted legal and public relations battle with New York Times reporter James Risen.

Former CIA agent Jeffrey Sterling was prosecuted under the Espionage Act for leaking information to Risen that showed up in his book, State of War. Prosecutors wanted Risen to testify that Sterling was his source, and Risen refused. After a three-year battle, prosecutors obtained a court order that Risen had no privilege to protect his source and could be compelled to testify. However, faced with the prospect that Risen would refuse and force the government to have him jailed for contempt, the prosecutors blinked. They decided not to call Risen, and convicted Sterling at trial without Risen’s testimony. Risen was never criminally charged or forced to testify, but condemned Obama as the “greatest enemy to press freedom in a generation.”

But probably the most notorious incident involving the press during the Obama years was the 2010 prosecution of State Department analyst Stephen Kim. Kim was indicted for leaking information about North Korea’s nuclear program to Fox News reporter James Rosen. Prosecutors later obtained a search warrant for Rosen’s email account to look for communications with Kim. In the search warrant affidavit they characterized Rosen as a criminal co-conspirator or aider and abettor for encouraging Kim to leak the classified information to him.

Legally this description was completely accurate, and Rosen was not prosecuted. But characterizing a journalist as a criminal co-conspirator in a search warrant affidavit caused a huge controversy and is still repeatedly cited as evidence that the Obama administration was hostile to the press. According to news reports, the Obama administration also considered prosecuting Assange for his work with Manning but ultimately declined, believing the case would come too close to treading on freedom of the press. But the Trump administration revisited that decision.

The legal theories used to prosecute Assange are largely the same as those contained in the Rosen search warrant: that he aided and abetted or conspired with the leaker who violated the law by disclosing the classified information. But the Assange indictment goes one step further by also charging Assange based on publishing a portion of the information, not just receiving it.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has further accelerated the pursuit of leakers. In 2017, Attorney General Sessions announced the Justice Department had tripled the number of leak investigations. When announcing the Assange indictment, DOJ officials said they have brought four leak prosecutions in two years, double Obama’s pace.

Is Assange a Journalist? That’s the Wrong Question

When announcing the Assange indictment, DOJ officials said they don’t consider Assange a journalist. Much of the commentary about the case suggests it should not be worrisome because Assange is not a true journalist. But whether or not he’s a journalist is really the wrong question. The First Amendment does not refer to “journalists” in the protections it provides for free speech and a free press. And the Supreme Court has made it clear that the First Amendment applies equally to the New York Times and to a pajama-clad blogger writing in his basement.

Defining who is a “journalist” is a thorny, and perhaps constitutionally insurmountable, problem. For years there have been efforts on Capitol Hill to pass a reporter’s shield law that would protect journalists from being compelled to identify their sources, at least in some cases. But those efforts have always stalled, due at least in part to the difficulty of defining who is a “journalist” entitled to the protection of the law.

Nearly fifty years ago, in the landmark case of Branzburg v. Hayes, the Supreme Court held that the Constitution does not create a reporter’s privilege. At the time, the Court noted that trying to define who is a “newsman” worthy of any such privilege “would present practical and conceptual difficulties of a high order” and would be a “questionable procedure.” That was at a time when the news media consisted largely of local newspapers, radio, and three television networks. In the age of the Internet, social media, and citizen journalism, those difficulties are exponentially greater.

A definition necessarily excludes someone and puts the government in the position of deciding who it deems a "real" journalist worthy of a special legal privilege. That process itself raises grave First Amendment concerns.

There are certainly ways in which Assange differs dramatically from a mainstream journalist. He generally just dumps leaked materials on the Internet with no screening, verification, or reporting. He acts more like an agent of a hostile foreign power than a reporter. Most of his activities seem worthy of little sympathy. As the Assistant Attorney General said when announcing the Assange indictment, no responsible person, whether or not a journalist, would disclose the names of confidential intelligence sources in a war zone, knowingly exposing them to grave danger.

But the issue is not whether Assange is a journalist or whether his behavior is reprehensible. It’s whether the legal theories used to prosecute Assange also could be employed to prosecute a mainstream journalist, and thus whether the Assange indictment creates a potentially dangerous precedent. The answer appears to be yes.

The Tension Between the Press and the Government

There has always been a healthy tension between the press and the government. The government tries to keep some secrets. Most would agree that it tries to keep far too many and that it classifies too much information. Sometimes it tries to keep information secret not because its release would really damage national security but simply because it would be embarrassing or politically damaging.

Our robust free press and investigative journalism have always played a vital role in fighting excessive government secrecy and ferreting out important information. Scandals such as Watergate and the government excesses during the Iraq war only came to light through the efforts of dogged journalists. In many such cases that work involves the journalists receiving, and reporting on, leaked classified information.

On the other hand, almost all would agree there are some secrets the government should be able to keep. Leaks of the most sensitive military and intelligence information could genuinely harm our national interests or put those serving our country in harm’s way. And if we agree the government must be able to keep some secrets, then we should be able to agree that in appropriate cases the government may prosecute those who illegally disclose such vital information and try to deter others from doing so.

It’s also clear there can be no absolute immunity for journalists from criminal prosecution related to their work. To take an extreme example, a journalist could not hire a burglar to break into an office to steal confidential files, publish them, and then claim immunity from prosecution based on freedom of the press. If Assange had obtained classified information and hand-delivered to agents of the Taliban, it seems clear that he could be prosecuted for espionage. Why should the result be different because he chose to deliver the materials by posting them on the Internet?

The Role of Prosecutorial Discretion

In the end, these cases are all about line drawing. An investigative journalist at a mainstream newspaper regularly receives classified material. He or she may request such materials from a source, even try to cajole the source into obtaining more such materials, directly or subtly. At some point such encouragement or active participation could cross the line into soliciting criminal activity. What prevents such cases from being charged, at least up to this point, is respect for the role of the press and the sound exercise of prosecutorial discretion.

Government officials went out of their way to emphasize this when announcing the Assange indictment. They noted that prosecutorial decisions in each case have to be evaluated on their specific facts, and that mainstream journalism has nothing to fear from the Assange indictment. But the legal theories are there, and always have been.

This really isn't that surprising. Many criminal statutes contain sweeping prohibitions that could potentially apply to a given case but prosecutors exercise their discretion not to pursue it. In particular, prosecutors traditionally have respected the role of the Fourth Estate. For example, although (as the Risen and Rosen cases demonstrated) journalists have no legal privilege to refuse to reveal their sources in federal cases or to shield their communications in general, DOJ has voluntary internal guidelines to ensure that seeking information from a reporter will be extremely rare and will require approval at the highest levels.

This respect for the role of the press is part of the healthy push and pull between the press and the government that has always existed. It’s probably true the Trump administration will not seek to expand the theories used against Assange to prosecute traditional journalists. Certainly there would be a huge outcry, even from the president’s friends in the conservative media. And there would be substantial constitutional defenses to any such case. This was not a routine leak, but one of the largest security breaches in U.S. history. And however we define journalism, most of Assange's actions stray far from that concept.

But reliance on prosecutorial discretion requires trust that discretion will be exercised dispassionately, with some wisdom, humility, and historical perspective. Considering this president routinely refers to the press as the enemy of the American people and accuses the press of treason, you can’t blame journalists for being a little nervous.