Prosecuting a President for Bribery After Trump v. United States

Presidential immunity complicates corruption prosecutions

After the Supreme Court’s decision on presidential immunity in Trump v. United States, many wonder whether it would still be possible to prosecute a former president for bribery. After all, the crime of bribery involves accepting something of value in return for being influenced in the performance of an official act, and the Supreme Court held that challenging official presidential acts is now largely off limits. In her dissent, Justice Sotomayor claimed that a president who took a bribe in exchange for granting a pardon would now be immune from prosecution. Is she right?

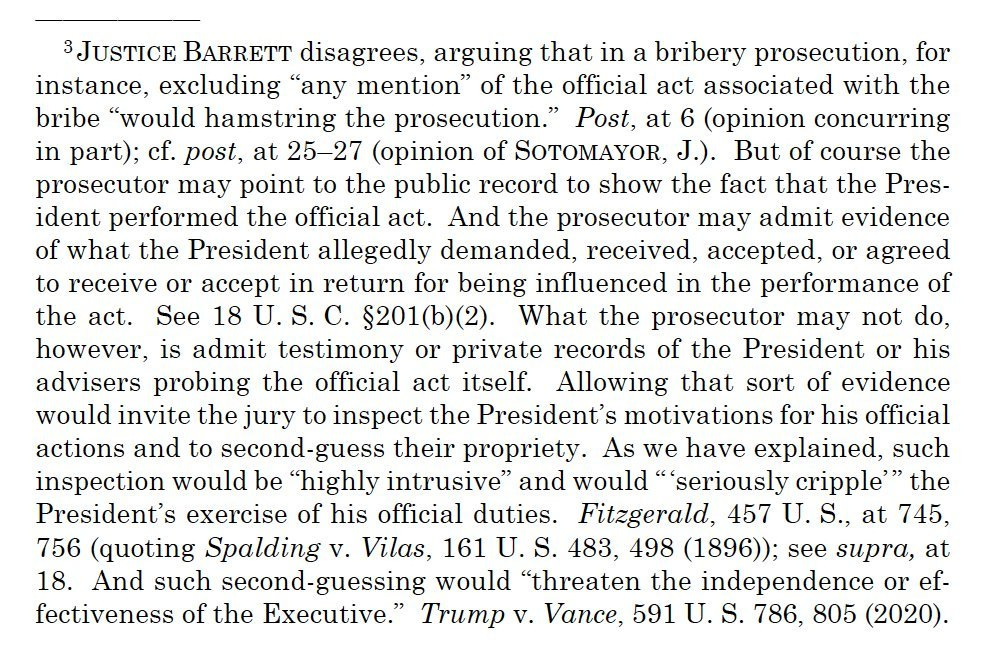

In connection with this question, legal commentators have been trying to decipher the cryptic footnote 3 of Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion:

This footnote is confusing, as is the related portion of the Court’s opinion. But I believe that, properly understood, it means a former president can still be prosecuted for bribery. Presidential immunity will make such prosecutions more challenging, but not impossible.

A couple of preliminary notes: my purpose here is not to critique this awful decision, but to explore its potential impact on future bribery prosecutions. If you’re interested in a more general discussion of the immunity decision, you can find that here:

In addition, although I may refer to prosecuting a president for bribery, what we are really talking about is prosecuting a former president for bribery after he/she leaves office. Under current Justice Department policy a sitting president may not be criminally prosecuted. Even if DOJ tried to change that policy, it seems likely that this Supreme Court would forbid such a prosecution.

The Crime of Bribery

To begin, it’s important to recognize that in a bribery case the crime is the agreement – the corrupt deal. It’s the promise to perform an official act in exchange for something of value. Once that agreement to sell the power of the public office is made, the crime is complete.

For example, imagine a Pentagon official who agrees to accept a bribe in exchange for steering a defense contract to the bribe payor. Suppose that after he makes the deal, the contract is cancelled for unrelated reasons, making performance of the agreement impossible. Or maybe the official is thwarted somehow and is unsuccessful, or gets cold feet and never follows through. None of these are a defense to the bribery charge. Whether or not the official act is ever performed is legally irrelevant. The crime was completed when the deal was made.

When you hear the term quid pro quo, or “this for that,” it refers to the agreement: if you promise to give me this, I promise to do that for you. But there is no requirement that the quo ever is performed.

Of course it would be helpful in many cases to be able to show that the corrupt deal was carried out. Performance of the official act can be compelling circumstantial evidence that the deal existed. But proving that the deal was fulfilled is not legally required.

This distinction is critical to the discussion that follows: the corrupt bribery agreement and the official act (if it even takes place) are two distinct events.

The Speech or Debate Clause

I believe it’s helpful to analogize this newly-created presidential immunity to the Speech or Debate clause. Unlike the president, members of Congress enjoy an immunity that is explicitly provided for in the Constitution. Article I, section 6, clause 1 states that for any speech or debate in either house, members of Congress “shall not be questioned in any other Place.” This immunity clause places proof of legislative acts off limits to prosecutors.

Suppose a Senator takes a bribe in exchange for agreeing to vote a certain way on a bill. Due to the speech or debate clause, prosecutors may not introduce evidence of the actual vote or of the Senator’s related legislative acts, such as a speech on the Senate floor or comments in a committee hearing. But in a 1972 case called United States v. Brewster, the Supreme Court ruled that prosecutors may still prove the Senator’s corrupt agreement to sell his vote -- and that’s the crime of bribery. The corrupt deal itself is not a legislative act protected by the Speech or Debate clause.

As a result, Speech or Debate immunity makes prosecutions of members of Congress more challenging, but not impossible. The case against New Jersey Senator Bob Menendez that is going on right now is an example. The court there ruled that evidence of some of Menendez’s legislative acts was prohibited by the Speech or Debate clause. But prosecutors were still able to put on substantial evidence of corrupt agreements that took place off the Senate floor, where Menendez allegedly agreed to sell the power of his office in exchange for cash and gold bars.

It appears that presidential immunity is best considered as something akin to speech or debate immunity for Congress. Prosecutors may not introduce evidence regarding the president’s official acts. But if the president made a corrupt deal to perform an official act in exchange for a bribe, prosecutors could still introduce evidence of that deal.

As an aside – it’s notable that although the Constitution explicitly provides some immunity for members of Congress, it provides no such immunity for the President. Speech or debate immunity is part of the Constitution’s system of checks and balances. It protects the legislative branch from political or otherwise unjustified prosecutions by a potentially hostile executive branch. It has its common-law roots in Parliament’s need for protection from the Crown.

When a former president is prosecuted, however, the case is brought by the president’s own former branch of government. The executive branch has its own institutional interests in ensuring that former presidents are not subject to routine or inappropriate prosecutions. Every president knows he or she could be next, and every president’s Justice Department has an interest in protecting the office of the presidency. The same checks-and-balances protections are not required.

You would think a Supreme Court that claims to believe in following the original intent of the framers would have found it significant that the framers included immunity for Congress but not for the president. You would think.

Parsing Footnote Three

The government argued that even if a president could not be prosecuted for official acts, prosecutors should still be allowed to introduce evidence regarding those acts to establish things like the president’s knowledge and intent for other allowable charges. The Court rejected that argument, holding that this would “eviscerate” the immunity it had just recognized and would allow prosecutors to do indirectly what they may not do directly: probe the president’s motivations for his immune official acts.

Justice Barrett concurred in all but that portion of the Court’s opinion, and that’s what led to footnote three quoted above. She argued that a bribery prosecution, for example, would be hamstrung and almost impossible if prosecutors can’t introduce evidence regarding the official act. Footnote three is the majority’s response to Justice Barrett’s concern. As confused as it is, it makes it pretty clear that the majority does not believe a bribery prosecution of a former president would be impossible.

The Chief Justice in footnote three says that although evidence related to the official act may be prohibited, “the prosecutor may admit evidence of what the President allegedly demanded, received, accepted, or agreed to receive or accept in return for being influenced in the performance of the act.” That language is right out of the federal bribery statute, 18 U.S..C. 201. That appears to mean prosecutors can prove the corrupt agreement – just as in a speech or debate case. And as we’ve been discussing, that’s all you need to establish the crime of bribery.

But the footnote goes on to say: “What the prosecutor may not do, however, is admit testimony or private records of the President or his advisers probing the official act itself. Allowing that sort of evidence would invite the jury to inspect the President’s motivations for his official actions and to second-guess their propriety.”

This is where the footnote gets really confusing. If you are allowed to introduce evidence of the corrupt agreement, isn’t that also evidence of the president’s “motivations for his official actions?” You’re proving that his motive for taking the action was that he was bribed to do so, and that would certainly second-guess the propriety of the president’s actions. That’s what has led some to suggest this passage means you really can’t prove a bribery case at all.

It’s not very clear, but the only way the footnote as a whole makes sense is if this prohibition on evidence about the president’s state of mind refers only to evidence surrounding the actual performance of the “official act itself.” It does not prohibit evidence of the president’s prior corrupt agreement, because that agreement by definition is not an official act – even though proving the corrupt agreement will also end up providing evidence of the president’s motives.

The agreement and the performance of the official act are distinct events, as evidenced by the fact that prosecutors don’t need to prove the latter to prove bribery. Prosecutors are still allowed to prove the corrupt agreement. There’s no other way to square footnote three’s statement that the government may introduce evidence of what the President allegedly demanded, received, accepted, or agreed to receive and accept as part of the deal.

This interpretation also aligns with the language of the Brewster case I mentioned above on the Speech or Debate clause. The Court in Brewster said that the clause prohibits inquiry into a legislative act or the “motivation for a legislative act.” But it also held that the clause did not forbid proof of a corrupt bribery agreement related to performing that act, even though that also involves evidence of the legislator’s ultimate motives. The limitation on proving the Senator’s “motivation” related to the legislative act itself, but not to the prior corrupt agreement.

Curiously, footnote three also says prosecutors could introduce evidence from the “public record” that the president performed the official act. You couldn’t do that in a speech or debate case – you can’t introduce evidence of the Senator’s vote, for example. In that respect, this new presidential immunity appears narrower than the speech or debate clause. The presidential privilege appears focused more on protecting the president’s personal communications and deliberations and not on whether the act itself took place.

Prosecuting a President for Bribery

So how would this all play out in a presidential bribery case? Let’s imagine a bribe in exchange for a pardon. The pardon power is one of the core executive powers expressly provided in the Constitution that the Court has declared absolutely immune from prosecution. It’s clear from the opinion that a president could not be prosecuted for granting a pardon. But what about for accepting a bribe to grant a pardon?

Suppose an individual (let’s call him Rudy) offers to pay the president $1 million for a pardon for any crimes related to efforts to overturn the 2020 election. The president says, “It’s a deal.” At that point, the crime of bribery is complete. Evidence of that corrupt agreement is admissible, according to footnote 3, as evidence of the president agreeing to receive and accept something of value in exchange for an official act.

How would prosecutors prove that deal? Well, maybe Rudy will later flip and testify. Maybe Rudy and the president will confirm the agreement in text messages or emails that can be admitted into evidence. Maybe other witnesses overheard the agreement or heard Rudy talking about it. Or maybe there will be enough other circumstantial evidence to prove the agreement. But it’s pretty clear from footnote 3 that prosecutors can try to prove it.

To be sure, proving the corrupt deal may be difficult, but that’s not new when it comes to public corruption cases. That’s what makes these cases so challenging. In a fraud case, for example, you have victims who are generally willing to come forward to help the prosecution and provide evidence regarding their dealings with the defendant. In a bribery case, there often will be no other witnesses. Neither party to the deal has any interest in helping the prosecution, and the “victims” – the public at large – have no idea the crime has occurred. Unless one of the participants in the bribe eventually agrees to cooperate, proving the deal will be challenging. That’s true with or without presidential immunity.

Now supposes that after the corrupt deal is made, the president tells his chief of staff, “I’m going to pardon Rudy because he gave me a million bucks. Please see that it gets done.” The chief of staff replies, “Yes sir, I’m on it.” That evidence about the act itself and the president’s communications presumably is not admissible, according to footnote three, because it is direct evidence from the president and his advisors about his motivations for performing the act itself. But that doesn’t mean prosecutors can’t prove the prior deal with Rudy, which constitutes the bribe. That corrupt agreement itself is not an official act.

Footnote three also says that prosecutors could introduce public records showing that the pardon was granted, which would provide further circumstantial evidence of the corrupt deal. What they apparently can’t do is introduce direct evidence of the president in the act of issuing the pardon, or of his communications with his chief of staff or others about that official act. That evidence about “the official act itself” is prohibited.

Bribery Prosecutions: More Difficult But Not Impossible

I think we are left with a doctrine of presidential immunity very similar to speech or debate immunity. Prosecutors can’t investigate and prosecute a president’s core official acts. But if a president makes a corrupt deal to perform an official act, prosecutors may investigate and present evidence of that deal to establish the crime of bribery.

Of course, a corrupt sitting president could also just pardon Rudy for the bribe and probably pardon himself as well, and those pardons would be unreviewable. But that’s a different issue.

This opinion makes prosecuting a corrupt president for bribery more difficult, just as the speech or debate clause makes prosecuting a corrupt Senator more difficult. But it’s still possible.

An interesting discussion which highlights the intricacies of legal thinking lost to the untrained public mind. A question:

Isn’t giving the POTUS the right to pardon himself the same as legally sanctioned placing of him/herself above the law? I don’t see how the framers could overlook potential immoral conduct as an obstacle to giving the POTUS a personal get out of jail free card.

Thanks for trying to make sense of a gobbledygook footnote and turning it into something intelligible. One would think, and rightfully expect, the high court to write with clarity so that at a minimum even trained lawyers would understand what the court is trying to communicate.