Senator Menendez and the Speech or Debate Clause

Update: On 9/28/15, the judge denied Menendez's motions to dismiss the indictment based on the speech or debate clause. Menendez is expected to appeal that ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Update 2: The Third Circuit denied Menendez's appeal on July 29, 2016. On December 12, 2016, he filed a petition for certiorari asking the Supreme Court to review his speech or debate claims.

Update 3: The Supreme Court declined to take Menendez's appeal on March 20, 2017. The case will now go back to the district court to proceed towards trial.

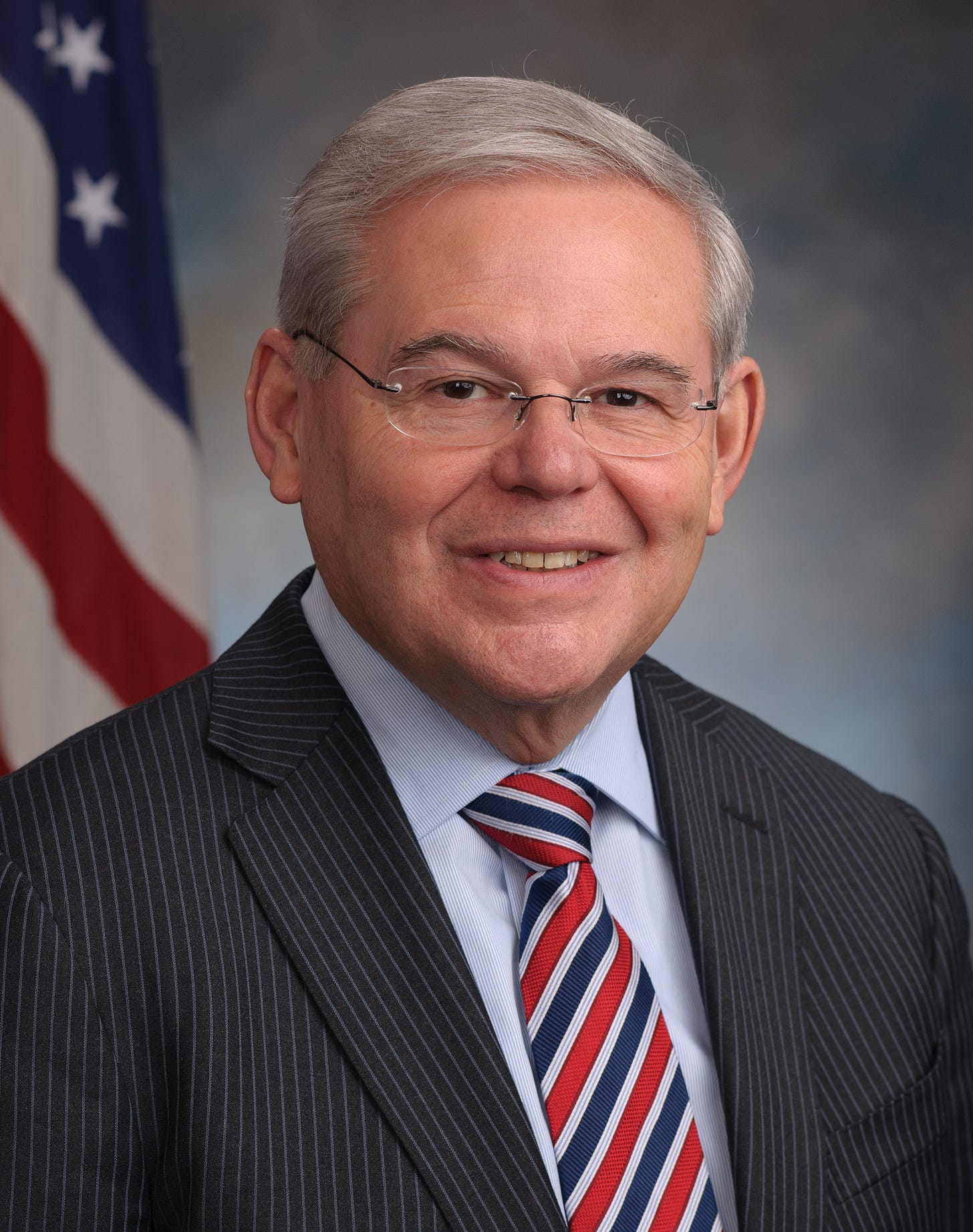

United States Senator Robert Menendez of New Jersey and his co-defendant Salomon Melgen were indicted last April on multiple counts of corruption. The indictment describes a bribery scheme: over a number of years, Melgen is alleged to have provided Menendez with numerous valuable gifts, including multiple trips on his private jet, repeated stays at a luxury villa in the Dominican Republic, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in contributions to various campaigns and a legal defense fund. In exchange, Menendez is alleged to have taken various official actions to benefit Melgen. (For a detailed analysis of the indictment, see my earlier post here.)

Since the charges were announced, some have wondered whether the Constitution’s speech or debate clause might shield Menendez’s conduct or provide him with a defense. The speech or debate clause is almost inevitably raised in any case involving a member of Congress, and has already been the subject of some preliminary skirmishing in the case. In the end, though, it seems unlikely to be much help to Menendez.

The Speech or Debate Clause: Protection for "Legislative Acts"

The speech or debate clause, Article I, Sec. 6, Cl. 1 of the Constitution, provides that “for any Speech or Debate in either house, [Senators and Representatives] shall not be questioned in any other Place.” The clause has a long and distinguished legal history. It was based on a similar provision in the English Bill of Rights of 1689, passed in response to the Crown’s nasty habit of arresting members of Parliament for sedition when they made speeches the king didn’t like. The framers considered the clause a key part of the system of checks and balances, because it protects members of the legislative branch from harassment or intimidation by the executive or by a hostile judiciary.

The Supreme Court has made it clear over the years that the protections of the clause extend not only to actual speeches and debates on Capitol Hill but to all “legislative acts” or acts within the “legislative sphere.” Legislative acts include things such as voting, actions taken in committee, preparing committee reports, talking to other Members concerning bills, and other activities directly related to the passage of legislation.

At the same time, it’s clear that the Clause does not bar inquiry into the actions of a member of Congress simply because those actions might be related in some way to his or her official duties. Nor does it provide Members of Congress with immunity from prosecution for official corruption. As long as the government can prove its case without reference to legislative acts, the speech or debate clause presents no bar.

A leading Supreme Court case interpreting the clause involved Alaska Senator Mike Gravel, who in 1971 convened a Senate subcommittee hearing at which he read extensively from the Pentagon Papers and placed the entire 47 volumes into the Congressional Record. He later arranged for private publication of the papers. A grand jury investigating possible criminal conduct in connection with the release of the papers subpoenaed an aide to Gravel to question him about these events, and Gravel moved to quash the subpoena.

The Court first held it was undeniable that Gravel himself could not be questioned about or punished for his behavior in the Senate. That was core speech or debate conduct. The Court also held that the protections of the clause must extend to legislative aides, if their conduct would have been a protected legislative act if performed by the Member himself. Accordingly, Gravel’s aide likewise could not be questioned in the grand jury about events that took place on the Senate floor.

The arrangement for private publication of the papers, however, was another matter. The Court noted that the speech or debate clause does not cover everything done by a Member of Congress, and the mere fact that things were done in an official capacity does not make them protected “legislative acts:”

The heart of the Clause is speech or debate in either House. Insofar as the Clause is construed to reach other matters, they must be an integral part of the deliberative and communicative processes by which Members participate in committee and House proceedings with respect to the consideration and passage or rejection of proposed legislation or with respect to other matters which the Constitution places within the jurisdiction of either House.

As a result, the Court concluded, the grand jury was free to inquire into areas such as how Gravel received the papers in the first place, as well as his arrangements for private publication. Even though he did these things in his capacity as a Senator, they were not legislative acts protected by the clause.

In a companion case to Gravel, United States v. Brewster, the Court stated that evidence will be barred only if it becomes “necessary to inquire into how [the defendant] spoke, how he debated, how he voted, or anything he did in the chamber or in committee.” Activities need not take place inside the Capitol to be protected however; other actions directly related to the legislative process, such as preparing reports or conducting investigations related to legislation, are also covered.

On the other hand, acts such as performing constituent services, writing newsletters, meeting with Executive branch agencies, and giving speeches outside of Congress, although part of a Member’s job, are not protected by the speech or debate clause. These activities are considered political in nature and not related to the core legislative duties of debating and enacting legislation.

Members of Congress under investigation often argue that virtually all of their activities have some role to play in the legislative process and should be protected, but courts generally reject such claims. If that were the standard, Members of Congress would end up virtually immune from prosecution for corruption or any other job-related misconduct. As the Supreme Court noted in Brewster, the Clause “does not prohibit inquiry into illegal conduct simply because it has some nexus to legislative functions.”

The key in any speech or debate case, therefore, is to determine whether proof of the charges will require any inquiry into protected legislative acts. Evidence concerning legislative acts will be prohibited, even if that ends up meaning the defendant may not be prosecuted at all. But if the government can prove its case without evidence of or inquiry into legislative acts, the case may proceed.

Speech or Debate in the Menendez Case

On the face of the indictment, the actions alleged to have been taken by Menendez and his staff do not appear to be legislative acts that would be protected by the speech or debate clause. The actions fall into three main categories:

Visas: In 2007 and 2008, Menendez and his staff contacted various embassy and State Department personnel on Melgen’s behalf, in order to help three different girlfriends of Melgen -- one from Brazil, one from Ukraine, and one from the Dominican Republic -- obtain visas to come to the United States. These efforts consisted of e-mails, phone calls and letters from Menendez and his staff in support of the visa applications.

Port Screening Contract: Melgen owned an interest in a company that had a contract with the government of the Dominican Republic to provide x-ray screening of all cargo entering Dominican ports. The contract, potentially worth many millions of dollars, had been tied up in disputes and work had not begun. Beginning in 2012, Menendez and his staff began contacting State Department officials to urge them to pressure the Dominican government to implement the contract. At one point Menendez allegedly met with an Assistant Secretary of State to discuss the issue, told him he was unsatisfied with the way State was handling it, and threatened to hold a hearing and call the Assistant Secretary to testify.

Medicare dispute: Melgen, a prominent Florida ophthalmologist, was embroiled for several years in a multi-million dollar dispute over his Medicare billings. He was allegedly taking an eye medication that came in a vial designed for a single patient and using it to treat two or three patients. He would then bill Medicare as if he had purchased a separate vial for each individual patient. When Medicare discovered this practice they began pursuing claims against Melgen for overbilling. Melgen was recently indicted in a separate Medicare fraud case in Florida, based in part on this same overbilling scheme. Menendez and his staff worked for several years to try to help Melgen resolve his dispute with Medicare. This included Menendez himself meeting with Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius and with Marilyn Tavenner, the acting director for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

There doesn’t seem to be much here that would raise a speech or debate clause issue. All of the actions described involve Menendez or his staff interacting with various executive branch agencies concerning matters that do not appear directly related to legislation. The Supreme Court has consistently considered such contacts with the executive branch to be political, rather than legislative, and not protected by the clause.

Menendez’s best hope will be to try to convince the court that his actions on behalf of Melgen were actually related to some broader, legislative policy issue that he was investigating. For example, some reports have suggested that Menendez will argue his meeting with Sebelius and other actions in the Medicare dispute were related to his work on the Senate Finance Committee, which oversees Medicare’s finances. In addition, the indictment notes that Menendez threatened to hold a hearing concerning the port contract dispute, and Menendez may try to argue that any steps he took concerning that contract were part of his investigation related to the potential hearing and Congressional oversight of the matter.

We caught a glimpse during the grand jury investigation of the type of arguments Menendez likely will make. Apparently two of Menendez’s aides refused to testify in the grand jury about certain actions they or Menendez took in the Medicare and port contract disputes, citing the speech or debate clause. The district court ruled that the privilege did not apply and that the aides must testify. On appeal, however, the Third Circuit sent the issue back to the trial court for further fact-finding concerning whether any of Menendez’s actions were related to his legislative activities. (This information was revealed when the Third Circuit’s order, which should have been under seal because it related to a grand jury investigation, was inadvertently made public for a period of time.) Apparently the government decided it could live without the evidence at the grand jury stage, and proceeded to indict the case without it rather than continue the fight.

Establishing that his contacts with different executive branch officials on Melgen's behalf were “legislative acts” seems like an uphill battle for Menendez. On the Medicare issue, for example, the indictment is full of references to staff memos and e-mails referring to Melgen’s Medicare problem and the “Melgen case.” The correspondence is all about Melgen’s particular dispute, not about any broader policy issues or proposed legislation. The paper trail may not support any after-the-fact attempts to argue that Menendez’s efforts were really about legislation, not about helping out his benefactor.

Defense motions in the case are currently due on July 20, and we will know more about Menendez's arguments then. Unlike most issues in a criminal trial, the burden of proving that the speech or debate clause applies falls on Menendez, not on the government. But even if he doesn’t prevail, Menendez can tie things up for quite a while. Orders concerning the application of the speech or debate clause may be appealed immediately, before trial. It’s clear from the pleadings already filed that both sides, as well as the judge, are anticipating such pre-trial appeals.

If Menendez loses on speech or debate before the trial judge his appeals could easily delay the trial, currently set for October 13, for a year or more. If the government loses on speech or debate, it will have to decide whether the evidence that ends up being excluded is so critical to the case that it needs to appeal, or whether it can proceed without it, as it apparently did in the grand jury. The bottom line is that the speech or debate clause seems unlikely to derail the Menendez prosecution in the end. But fights over the clause may well delay the trial well into 2016 or beyond, while Menendez, whose current term runs through 2018, continues to represent the Garden State in the United States Senate.