The Weekend Wrap: April 28, 2024

Immunity delays in D.C. and a historic trial in New York

Welcome to the Weekend Wrap! Here are the week’s white collar highlights:

Trump Prosecutions

D.C. Federal Case - January 6 Allegations

On Thursday the Supreme Court heard nearly three hours of arguments on Trump’s claim of absolute presidential immunity. In the end, Trump’s attorneys probably considered it a pretty good day - not because they will ultimately prevail, but because just by getting the Court to take up the issue they have already achieved Trump’s primary goal: delay.

As Justice Elena Kagan pointed out, our entire constitutional system is based on the fact that we have a president, not a king, and the president is subject to the law as is every other citizen. Presidents take action with the background understanding that if they intentionally commit a crime while carrying out their duties, they are potentially subject to prosecution. Given this fundamental principle, it was disheartening to hear so many justices entertain the idea that, in some circumstances, the president may indeed be above the law.

It seems pretty clear the Court will not agree with Trump’s claim of absolute immunity for official acts. But several of the justices appear interested in holding that there is some immunity for certain core presidential responsibilities, such as those explicitly named in the Constitution.

The Court could make this simple: it could say: “There may be some fundamental presidential duties where some degree of immunity would be appropriate. But we will leave that difficult question for another day. Whatever the scope of official duties that might be entitled to immunity, the actions alleged in this indictment fall well outside that scope. Therefore presidential immunity, to the extent it exists, is not an issue in this case and this trial can proceed.”

That would be the proper outcome. The Court doesn’t usually reach out to decide difficult constitutional issues if it doesn’t have to. But a number of the conservative justices appear willing to do just that here. They professed concern about future cases and future presidents and appear to want to resolve issues far beyond the scope of this case. Justice Gorsuch said he feels they are writing an opinion “for the ages.” That’s just wrong. All they have to do is resolve this particular case.

As they often do, the Justices relied on a “parade of horribles,” speculating about future presidents being prosecuted by political rivals for their official acts. Arguing for the special counsel’s office, Michael Dreeben said there were adequate protections in place to prevent that, including professional and ethical standards within the Justice Department, the requirement of a grand jury indictment, and the Executive branch’s own interest in preserving presidential authority. He also noted there may be unique legal defenses available to a president in some cases, such as a “public authority” defense for ordering military actions. But the conservative justices did not seem convinced these are adequate. They were quite willing to assume that future prosecutors would routinely ignore these standards and safeguards to pursue political rivals - despite that never having happened before.

I think Dreeben’s proposal makes sense: don’t recognize any form of presidential immunity, for which there is no constitutional or historical basis, but recognize that there may be legal defenses available only to the president that could come into play if a president is prosecuted for an official act. But I’m not sure a majority of the court is going to agree with him.

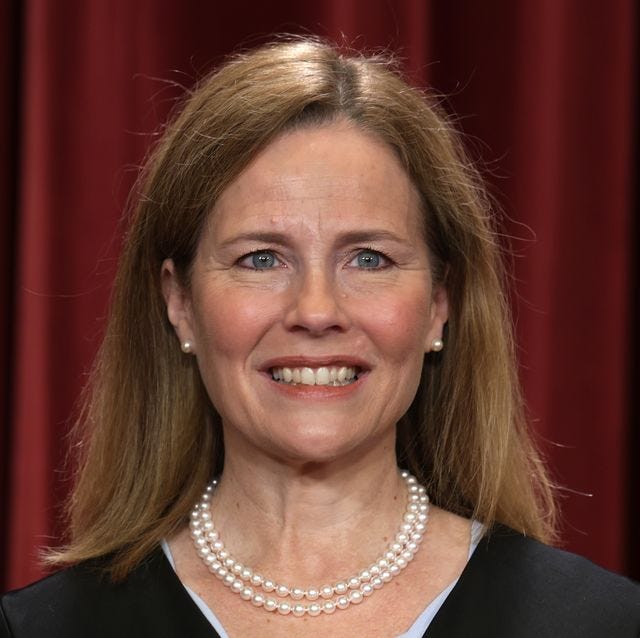

Justice Amy Coney Barrett (Credit: Getty images)

Swing vote Barrett? Everyone, including Trump’s attorney, agrees a former president can be prosecuted for purely private misconduct. Trump appointee Amy Coney Barrett (who of the three Trump-appointed justices was by far the most hostile to Trump’s position) walked through a number of allegations in the indictment, such as conspiring with a private attorney to prepare slates of phony electors, and got Trump’s attorney to agree that those sounded like private conduct. That seemed to open up the possibility of a ruling that although some official acts might be entitled to immunity, almost all of the acts alleged here are private acts of a candidate, not a president.

The three liberal justices, Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson, appeared solidly in the no-immunity camp. Chief Justice Roberts was hard to read, and asked relatively few questions. At times he seemed skeptical of immunity even for official acts. For example, he said that appointing an ambassador is a key presidential function, but immunity for official acts might mean a president could appoint someone in exchange for a bribe and not be prosecuted, which can’t be correct. On the other hand, he was quite critical of the D.C. Circuit opinion flatly holding there is never presidential immunity under any circumstances, and suggested further analysis was required.

Barrett could end up joining the liberals and the Chief in a majority opinion finding that certain official acts are entitled to immunity but private acts are not, and sending the matter back to the lower court to determine whether any of the alleged acts in this indictment qualify as “official.” If particular acts by Trump, such as trying to replace the attorney general or pressuring Mike Pence, are considered “official acts,” the government’s ability to introduce evidence of those acts might be limited. Or prosecutors may be able to introduce evidence of those acts to show Trump’s intent, but the jury would be instructed they can’t rely on those acts to find Trump criminally liable.

But for the trial judge to sort out which acts are “official” and which are not could take some time.

Disorder in the Court: There were some bizarre moments during this argument. At different points, Trump’s attorney argued that a president ordering the assassination of a political rival or ordering the military to stage a coup might be considered official acts that would be immune from prosecution. As election lawyer Marc Elias put it:

Justice Alito was by far the furthest “out there” when it came to apparent willingness to agree with Trump’s claims. He tried to flip the argument against immunity back on the government by saying (with no apparent sense of irony) that if presidents are not immune from prosecution, then a president might be more likely to try to remain in office unlawfully because he will fear being prosecuted if he leaves. He also huffed that presidents must make a lot of difficult decisions and that the government was arguing that if they make a mistake they can be prosecuted and it’s no big deal. Dreeben had to politely remind him that honest mistakes don’t generally lead to criminal prosecution.

Justice Kavanaugh was engaged in his own little side project, a variation on what conservatives call the “clear statement rule.” He suggested that only criminal statutes that expressly specify they apply to the president could be used to prosecute a former president, because then the president would be on notice that he might be subject to prosecution. (Currently almost no statutes expressly say that they apply to the president - probably because, up until now, it was assumed that the president, like every other citizen, is already on notice that he can’t violate the criminal law.) That would mean a former president could not be prosecuted for bribery or murder, for example, because those laws don’t explicitly say they apply to the president. Fortunately, none of the other justices seemed particularly interested in going down this road with Kavanaugh - but watch for at least a concurrence from him making this argument.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson had some strong moments. In response to the argument that without immunity a president might be reluctant to take bold, decisive action for fear of criminal liability, she pointed out that granting immunity created a potentially greater problem: a president who could turn the Oval Office into crime spree central with nothing to deter him: “If the potential for criminal liability is taken off the table, wouldn’t there be a significant risk that future presidents would be emboldened to commit crimes with abandon while they’re in office?”

In the end, as I said, I don’t think the Court is going to go along with full immunity. But it may (unnecessarily) write an opinion that seeks to outline the full parameters of presidential immunity and then send the issue back to Judge Chutkan to apply those new parameters to this case. Depending on what the opinion requires, she might be able to do that fairly quickly, or it might result in substantial additional delays.

By waiting to take the case as long as is did and then not putting it on a particularly fast track, the Court has already given Trump much of what he realistically hoped to achieve. If the Court now sits on its decision until the end of its term in late June or even early July, it will have become nearly impossible for the case to be tried prior to the election. The justices could decide quickly and issue an opinion in May, but given their pace thus far I don’t hold out much hope for that.

Overall, as I said - very disheartening.

New York State Case - Hush Money/False Business Records

The first week of trial is in the books in New York. In opening statements, the DA alleged that Trump was the leader of a criminal conspiracy to influence the 2016 election — even though there is no conspiracy charge in the indictment. As I’ve discussed before, prosecutors are trying to dress up the rather trivial charges of falsifying internal business records by arguing the case is really about election interference. The defense took a pretty aggressive posture in its opening, arguing that the records are not false and that Michael Cohen, Stormy Daniels, and everyone else accusing Trump is lying.