Emoluments, Bribery, and the Qatari Jet

Trump takes corruption to new heights

This week the Trump administration announced that the Qatari royal family intends to give Trump a lavishly-decorated 747 worth $400 million that has been described as a “palace in the sky”. Trump reportedly plans to use it as Air Force One during the remainder of his presidency. When he leaves office, ownership of the plane will be transferred to the Trump presidential library. Trump claims he would no longer use the plane after leaving office, but presumably there would be little to stop him should he break that promise.

(Ben Curtis/AP)

This plan understandably has drawn vehement protests from Democrats, some of whom have taken to calling the plane “Bribe Force One.” Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer just announced he is placing a hold on all Trump Justice Department nominations until the administration answers questions about the deal. Even a few Republican senators have started to question the wisdom of Trump accepting such a massive gift from a foreign government, and some leading Trump supporters on the MAGA right have attacked the deal on social media.

Critics argue that accepting the plane would violate the foreign Emoluments Clause in the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits federal officials from accepting gifts or titles from foreign governments. That clause is found in Article I, Section 9, Clause 8:

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States; And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatsoever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.

Other have suggested the proposed gift would violate federal bribery law, which prohibits federal officials from accepting anything of value in exchange for agreeing to be influenced in the performance of an official act.

Trump, of course, is no stranger to such controversies. When he was first elected in 2016, his international business holdings immediately raised concerns about possible violations of the Emoluments Clause. Critics were alarmed over the possibility that foreign governments could seek to curry favor with the Trump administration by granting him favorable business deals in their own country or by spending lavish sums at Trump properties, including his hotel located near the White House in Washington, D.C. Those concerns proved to be well-founded.

But now, with this proposed airplane deal, Trump has taken the corruption to a whole new level.

Bribery vs. the Emoluments Clause

The foreign Emoluments Clause is related to the crime of bribery. The underlying concern of each is divided loyalty; that federal officials might act not in accordance with their obligation to do what is best for the country but to serve some private interest or reward those who have personally enriched them.

Although the two are related, the Emoluments Clause is more sweeping in its prohibitions than criminal bribery law. Back in 2016, after Trump was first elected, I wrote this explainer on the Emoluments Clause and bribery and how they differ. This was written before Trump took office and before we knew the extent of his willingness to profit from the presidency, so in hindsight it sounds a bit too hopeful in spots. It was also, of course, written before the Supreme Court’s presidential immunity decision last year called into question whether a president could ever be charged with bribery. But despite that, if you’re looking to understand the Emoluments Clause and how it relates to bribery, the post still holds up pretty well:

The Emoluments Clause, Bribery, and President Trump

Like a previously unknown contestant on “The Apprentice,” the Emoluments Clause has been catapulted to stardom by Donald Trump. There has probably been more written about this obscure section of the Constitution in the past few weeks than in its entire previous 229-year history.

During the first Trump administration, several lawsuits were filed based on claims that he had violated the Emoluments Clause. The cases bogged down over questions about who had standing to sue and other legal issues, and dragged slowly through the courts. Once Trump lost the 2020 election the Supreme Court ordered that the remaining cases be dropped because they were moot now that Trump was no longer president. So we still don’t have any definitive court rulings on the prohibitions of the clause or who has standing to sue to enforce it.

Bondi Signed Off? Then it Must Be OK

Attorney General Pam Bondi reportedly has written a memo concluding it would be legal for the government to accept the plane from Qatar (although we have not seen the memo). Bondi, by the way, previously worked as a lobbyist for the government of Qatar, which paid her $115,000 per month. In a normal world that would have caused the attorney general to recuse herself from reviewing this transaction - but ethical notions such as recusal seem almost quaint in this administration.

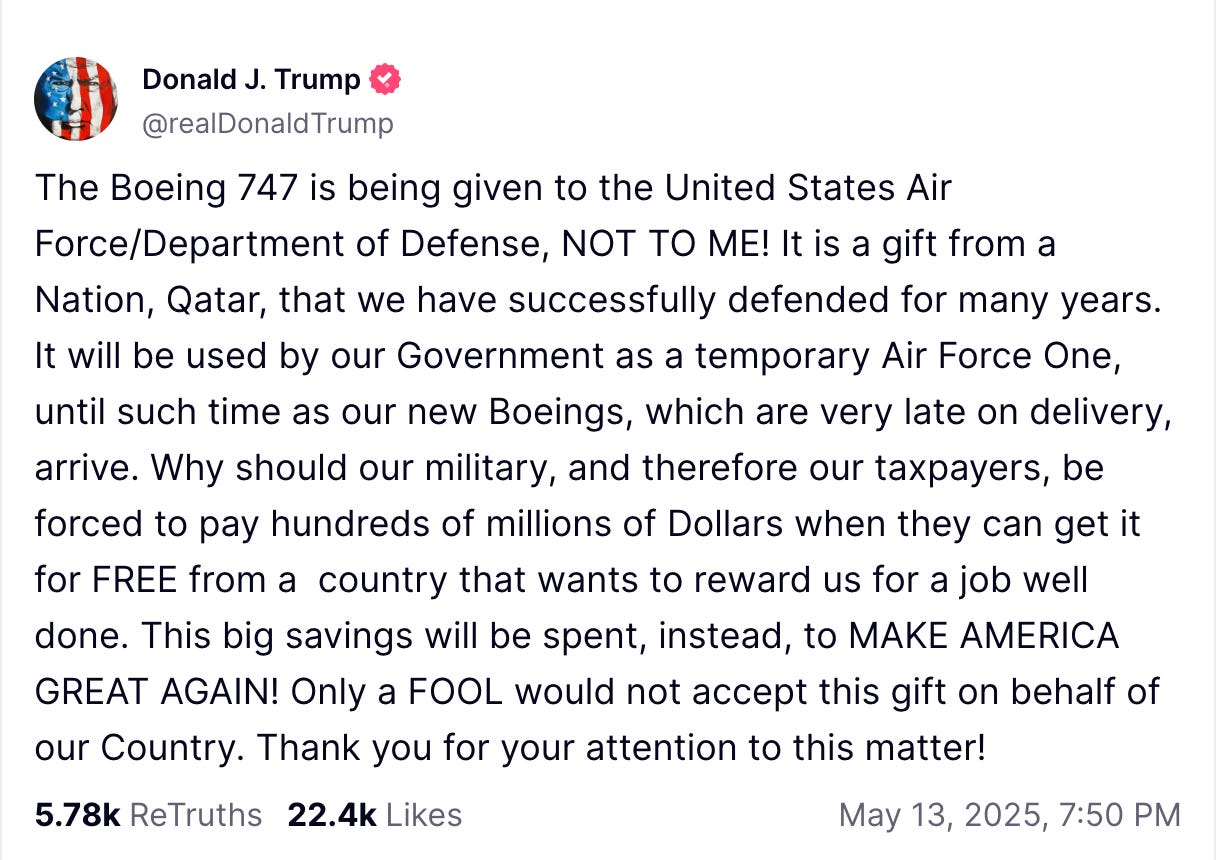

Bondi reportedly has concluded the gift would be lawful because the plane would be owned by the Air Force and then transferred to Trump’s presidential library foundation and would not be given to him personally. Trump has latched on to this defense, calling the plane a gift to the nation from a grateful Qatar:

Bondi also reportedly concluded that accepting the plane would be lawful because it is not being given in exchange for any particular action by Trump.

The latter point relates to whether the gift would violate federal criminal bribery law, which requires a link between the thing of value and a specific official act. Of course, the Supreme Court’s 2024 decision on presidential immunity might suggest this doesn’t matter, because Trump could never be prosecuted for bribery in any event. But as I argued here, I believe that even after that decision, prosecution of a former president for bribery would still be possible:

But putting questions of immunity aside — and much as it pains me to write these words — Bondi is probably right on the legal question of bribery. Remarkably enough, thanks to decades of Supreme Court decisions gutting federal corruption laws, it would not be a bribe for the government of Qatar to give Trump a $400 million plane — or even to give him $400 million in cash — just to cozy up to him. Such a gift would not violate federal bribery law unless the government could link it to an agreement by Trump to be influenced in performing some particular official act, a quid pro quo. Showering an official with gifts with the general hope of currying favor with that official is not be enough.

This seems bizarre, I know. But the legal restrictions imposed by the Supreme Court have made prosecuting public corruption extremely difficult, and Congress has failed to correct the problems. Current law leaves massive loopholes that allow private interests to purchase influence over and access to public officials. (If you want to read more about the sorry state of our federal public corruption laws, you can check out my New York Times column here or my earlier blog post here.)

I think Bondi is on far shakier ground when it comes to the Emoluments Clause. It’s true that the clause, by its terms, prohibits only the official himself or herself from receiving the gift. But here it’s clear that Trump is the intended beneficiary; it is effectively a gift to him personally. And as Commander in Chief of the Air Force, he would have the power to control how and when the plane is used for his benefit. Claiming this is not a gift to Trump based on who holds formal title to the plane ignores the reality of what’s happening. That said, if we found someone with standing to sue, I wouldn’t be terribly surprised if there were five votes for that defense on the current Supreme Court.

But whether Bondi’s legal defenses ultimately would hold up is not really the point. The question here isn’t whether the conduct is strictly lawful. I often tell my students there is a great deal of corrupt, sleazy, unethical conduct that may not be criminal, but that doesn’t make it right. That’s the case here: accepting the plane would be corrupt, pure and simple.

Bribery law is concerned with the prospect that a federal official will act not to serve the public interest but to benefit those who are paying him off. The Emoluments Clause is concerned with the prospect that U.S. government officials might feel more loyal to foreign governments that are enriching them than they do to the American people, and might act accordingly. All of those same concerns are squarely implicated by the Qatari plane deal. It clearly violates the spirit of these prohibitions, whether or not Trump might have a technical legal defense if a court case were filed.

Corruption is a broad concept that goes beyond the strict terms of legal texts or the evidentiary burdens of criminal trials. Here the corruption is obvious. Qatar isn’t doing this out of the goodness of its heart, or because members of the royal family are big fans of The Apprentice. Qatar wants things from the United States, including military assistance, support for its policies and actions in the Middle East, and favorable investment opportunities. Trump is in a position to give those things to his new benefactors.

In addition, the Trump Organization and Trump family have enormous business and financial interests in Qatar, including recently-announced plans to build a golf resort there worth more than $5 billion. The conflicts of interest and potential for using the office of the presidency for personal enrichment are immense. With that kind of money at stake, do we have confidence Trump will be making decisions regarding Qatar based on what’s in the best interest of the United States, rather than what’s in his own financial interest? As Trump might say, “only a FOOL” would believe that.

By the way, does anyone else recall how Republicans spent four years yelling about and investigating claims — which turned out to be completely false — that the Biden family had business ties to Ukraine worth a few million dollars? It turns out even if that had been true, it would have been mere chump change. And of course, most of those same Republicans are meekly silent now, as we watch the U.S. president and his family growing ever richer from their financial ties to Middle Eastern nations.

This level of financial entanglement between a president and a foreign nation would have been unthinkable in the past. Arguments about whether it is strictly legal are almost beside the point. We hold our public officials to a higher standard than simply being able to say that a court ultimately determined their actions were not unlawful — or at least we used to. Prior administrations of both parties would have rejected a deal like this out of hand, based on the mere appearance of potential impropriety. Once again, with an administration that openly flaunts its improprieties, that idea seems almost quaint.

So much of ethics, good government, and the rule of law depends on norms and traditions that have been recognized for generations but are not necessarily embodied in statutes. Their effectiveness depends on having people of good character in the government who are committed to upholding them and who believe public service is a public trust. This jet deal is just one more example of what happens when you put someone in office who cares nothing for those norms and ideals and is happy to trample them while daring people to try to stop him.

Professor Eliason, your discussion of the federal bribery law calls to mind the Big Law "settlements" from earlier this year. What's your take on the legality of those? The President received a thing of value (hundreds of millions of dollars in legal services), and in return was influenced in the performance of an official act (declined to revoke security clearances, left in place government contracts, etc.). Is official inaction distinct from official action?