The Weekend Wrap - August 27, 2023

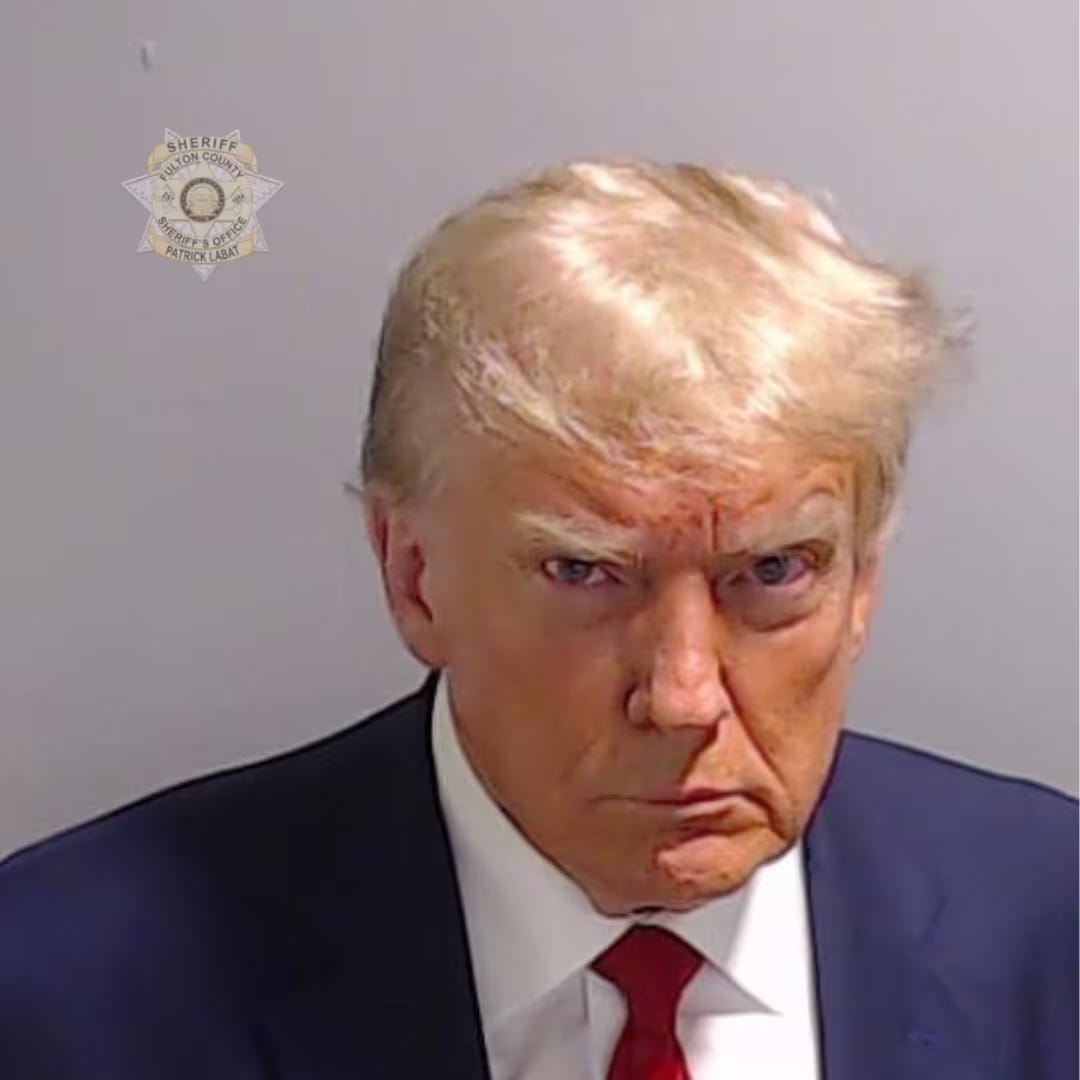

History's most famous mugshot

Welcome to the Weekend Wrap! Here are last week’s highlights.

The Trump Prosecutions

Georgia state case

The biggest Trump news this week came from Georgia. On Thursday Trump turned himself in for booking and processing. Bail was set at $200,000. This is the first case in which Trump had to post bail. It’s also the first time he’s had a mugshot taken, and it quickly became the most famous mugshot in history.

It’s a big, beautiful mugshot. Many people are saying it’s the greatest mugshot ever - truly amazing. Anyway that must be how Trump feels, because he wasted no time sharing it online, plastering it on t-shirts and other merch, and using it to raise money.

Trump’s release conditions, imposed in an order signed by Judge McAfee, include very strict requirements that he “perform no act to intimidate any person known to him . . . to be a codefendant or witness in this case or to otherwise obstruct the administration of justice.” This restriction includes “direct or indirect threats” on social media, whether in his own posts or sharing posts from others.

It's almost impossible to imagine Trump will not violate these conditions. When that happens, it will be very interesting to see what the judge does in response. The options include increased restrictions and sanctions up to and including revoking Trump’s bond and ordering him detained pending trial. That would be a gutsy move for a state court judge and would no doubt lead to another flurry of unprecedented legal fights. It would also risk turning Trump into a martyr, which may be exactly what he wants politically (although he certainly doesn’t want to spend time locked up in Atlanta’s jail).

I suspect the judges in all his cases will do whatever they can to avoid that kind of spectacle. But we can be pretty sure Trump is going to push the boundaries and put them to the test.

The other eighteen defendants have also turned themselves in for booking. Discovery and other pretrial matters will now begin.

Removal: You’ll recall last week we discussed how Trump’s former chief of staff Mark Meadows is seeking to remove his case to federal court. (If you want a deeper dive on removal and how it might play out in this case, Lee Kovarsky has this helpful post on Lawfare.)

DA Willis filed her opposition last week. She argued that the president has no role in monitoring state elections so Meadows couldn’t have been performing his federal duties, as required for removal. But if he thought he was, she pointed out, he was violating the Hatch Act, which prohibits federal employees from engaging in campaign activities. So no matter how you look at it, Meadows should be cooked.

The hearing on his petition is tomorrow, and we should get a better idea of what the judge is thinking.

Former DOJ environmental attorney Jeffrey Clark and three of the Georgia fake electors have also filed motions to remove their cases to federal court, following Meadows’ lead. Clark’s pleading is a political screed, complaining that prosecutors are simply out to get Trump and to destroy Clark’s reputation in the process. His petition should suffer from the same defects as Meadows’ and is arguably even weaker. As the acting head of DOJ’s Environment and Natural Resources division, his federal duties had nothing to do with investigating state elections.

But at least Meadows and Clark were federal employees. The fake elector defendants are state GOP operatives, but nevertheless are seeking the removal remedy meant for federal officials. They argue they are entitled to removal because everything they did was at the direction of Trump’s lawyers – helpfully throwing some co-defendants under the bus, which prosecutors always like to see. They also argue that presidential electors qualify as federal officials for purposes of removal. There’s just one tiny little flaw in this argument: they weren’t presidential electors!

I mean, “Hello” – that’s the basis of the entire case against them. They were fake electors. I don’t think their argument that they were acting as federal officials is going to get them very far.

Trump is widely expected to seek removal as well, but has not done so yet.

Speedy Trial: One of the Georgia defendants, attorney Ken Chesebro, moved this week for a speedy trial. Chesebro was deeply involved in the fake electors scheme and wrote several key memos outlining how it could work to disrupt the vote count on January 6 and hand the election to Trump. He is facing seven counts of conspiracy, including the lead RICO conspiracy charge.

Chesebro proposed a trial date in early November. DA Fani Willis responded with a proposal that all nineteen defendants go to trial on October 23. This resulted in a lot of online commentary along the lines of, “Oh, snap, Willis really called his bluff - she showed him”! But actually the opposite is true.

To say Willis called Chesebro’s bluff implies that she had a choice. She didn’t. Under Georgia law, Chesebro has a right to go to trial by early November if he makes that demand. If Willis didn’t comply, the charges would be dismissed. It’s actually Chesebro who potentially called Willis’ bluff. Instead of trying to delay as long as possible like Trump and probably most other defendants, Chesebro said he wants his day in court ASAP.

I’m a little surprised defendants don’t do this more often. It’s a gutsy tactical move but it could pay off. It holds prosecutors’ feet to the fire. They may end up being rushed and miss things or make mistakes that will work to the defendant’s advantage. Remember that the prosecutors always have the burden of proof. They are the ones who have to put on the case. The defense doesn’t need to put on a case at all if they don’t want to – they can just sit back and try to poke holes in the government’s case at trial.

Consider one example: in July 2008 Alaska Senator Ted Stevens was indicted on corruption charges. In an unusual move, he too insisted on a speedy trial, saying he wanted to clear his name before the 2008 election. His trial was that October - lightning speed for a complex case. He was found guilty and lost his re-election bid. But the prosecutors made significant errors during discovery and trial that later led the Justice Department to dismiss the entire case. I suspect the fact that the prosecutors had to scramble to get ready in a very short period of time contributed to those errors.

Prosecutors who indict a case like this should be prepared to go to trial very soon. But they may assume they will have many months to prepare and that the defendants will not be in any hurry. Chesebro is saying, “You indicted me? OK, let’s roll. Let’s see what you’ve got.” I think it could be a smart move.

In response, Judge McAfee set a trial date of October 23, but only for Chesebro. On Friday Trump attorney and conspiracy-monger Sidney Powell (of “release the Kraken” fame) also filed a demand for a speedy trial. It’s unclear whether any other defendants will seek to join them. We know Trump doesn’t want to – he has already moved to sever his case from any defendants who demand a speedy trial.

Willis knows about the Georgia speedy trial act, of course, so presumably she is ready to go. She is certainly giving every indication that she is. Even so, there’s a downside for her in having to try the case more than once (although that was probably inevitable, with 19 defendants). In addition to the time and resources required for multiple trials, the other defendants will benefit from being able to sit back and watch a preview of the case against them.

This could also all be a prelude to plea negotiations. Chesebro could be thinking he can increase his leverage and get a better deal by cutting himself loose from the rest of the pack and being the first scheduled for trial. That could be a smart move too, if he is thinking about cooperating.

Florida Federal Case

There was more bad news for Trump in the Florida Mar-a-Lago documents case last week. Prosecutors revealed that during their investigation a Trump employee who monitored the security cameras at Mar-a-Lago changed his testimony and implicated Trump and the other defendants in trying to destroy surveillance camera footage.

The switch came after the employee, Yuscil Taveras, ditched the lawyer Trump was paying for and hired his own counsel. Taveras is described as “Trump Employee 4” in the indictment. (See paras. 80-87) In the grand jury Taveras initially had denied any knowledge about efforts to erase the video footage. After getting his own lawyer, he recanted his earlier testimony and implicated the defendants in efforts to erase the videos that had been subpoenaed by the grand jury.

This is reminiscent of the evidence provided by Cassidy Hutchinson, the former aide to Mark Meadows, during the Congressional January 6 Committee hearings. You may recall she reported that her Trump-paid attorney had coached her to claim she did not recall things that she did in fact recall, in order to protect the former president. She ultimately fired that attorney, hired her own, and was a star witness against Trump.

As we’ve discussed before, this is part of a pattern in Trump world. His PAC has spent tens of millions on legal fees for those under investigation in the various cases against the former president. Team Trump pays for their lawyer in an effort to keep them close and loyal. As another example, the Florida superseding indictment notes that after being reassured by others that co-defendant Carlos De Oliveira would remain “loyal,” Trump called De Oliveira and told him he would pay for his lawyer.

This revelation about Taveras came in a government filing related to its request for a hearing to determine whether co-defendant Walt Nauta’s attorney has a conflict of interest based on his representation of others who may be government witnesses at trial. It turns out the same attorney was also the Trump-provided lawyer who represented Taveras before he was fired and Taveras recanted his false testimony.

In that pleading the government also responded to the judge’s inquiry we discussed a couple of weeks ago, about why prosecutors had continued to use a grand jury in D.C. after the case was indicted in Florida. As expected, the reason was to investigate possible perjury before that D.C. grand jury, including by Taveras – charges for which venue would only be proper in D.C.

The Florida case already looked to be the strongest of the four Trump indictments. This anticipated testimony from Taveras makes it even stronger. Imagine what he will say on the stand when asked to explain why he lied initially, then fired the Trump lawyer and told the truth. Absolutely devastating evidence of obstruction of justice.

Nauta and De Oliveira have to be considering whether they, too, should cut themselves loose from team Trump, get their own attorney, and try to get the best deal that they can in exchange for cooperation.

D.C. Federal Case

Last week we mentioned how Donald Trump’s attorneys had proposed a trial date in 2026, citing the need to review voluminous discovery and scheduling conflicts with Trump’s many other legal proceedings. On Monday the government responded, arguing:

In service of a proposed trial date in 2026 that would deny the public its right to a speedy trial, the defendant cites inapposite statistics and cases, overstates the amount of new and non-duplicative discovery, and exaggerates the challenge of reviewing it effectively.

Prosecutors noted that much of the discovery material was duplicative or of marginal relevance, and that much of it had come from Trump himself or was publicly available. They argued that modern electronic discovery tools make it possible for the defense to review it in a timely way. They also noted how they had gone out of their way to organize discovery for the defense and to “front load” their production with the most important material for trial, to help move things along.

Prosecutors maintain that their original proposal to begin the trial on January 2 remains reasonable and will protect both Trump’s and the public’s right to a speedy trial. Judge Chutkan should address these scheduling issues at the status hearing on Monday.

Other White Collar News

Covid Fraud Prosecutions

Last Wednesday Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco delivered some remarks about the Justice Department’s ongoing efforts to fight Covid-19 fraud. Trillions of dollars in emergency relief went to individuals and businesses to help them through the Covid-19 crisis. Any programs that big, passed and implemented in a hurry under crisis conditions, are going to be a ripe area for fraud – and the fraudsters did not disappoint.

The Attorney General formed the Covid-19 Fraud Enforcement Task Force in May 2021. The Justice Department has also formed inter-agency strike forces to focus on Covid-19 program fraud in a number of states. Monaco announced that since the beginning of the pandemic DOJ has brought criminal charges against nearly 3,200 defendants with alleged losses totaling about $1.7 billion. The Department has also seized nearly $1.4 billion in stolen relief funds through civil enforcement actions.

This work is ongoing and we can expect to keep seeing these cases for several years.

Cryptocurrency and Criminal Law

The intersection of cryptocurrency and criminal law continues to provide interesting stories, as law enforcement and legal theories struggle to keep pace with this new technology.

On Wednesday the founders of Tornado Cash Service, a cryptocurrency mixer, were indicted for conspiracy to commit money laundering and related charges. Prosecutors allege that Roman Storm of Washington and Roman Semenov of Russia knowingly used Tornado Cash to facilitate the laundering of more than $1 billion in illicit funds, including hundreds of millions from a sanctioned North Korea cybercrime group.

Cryptocurrency transactions take place on a public blockchain that others can view, which makes it difficult to hide what you are doing. A cryptocurrency mixer or tumbler takes different incoming streams of cryptocurrency, mixes them together, and then sends the crypto back to designated addresses, making it more difficult to trace the original transactions. That makes it an ideal service for those who wish to conceal the source of their criminal proceeds – the very definition of money laundering. The indictment alleges the defendants deliberately failed to follow anti-money laundering measure and “know your customer” rules designed to safeguard against such activity.

Announcing the indictment, Attorney General Garland said: “These charges should serve as yet another warning to those who think they can turn to cryptocurrency to conceal their crimes and hide their identities, including cryptocurrency mixers: it does not matter how sophisticated your scheme is or how many attempts you have made to anonymize yourself, the Justice Department will find you and hold you accountable for your crimes.”

In other crypto news, Nate Chastain was sentenced to three months in prison last week after being convicted last May in what the Justice Department misleadingly touted as the first crypto “insider trading” case. Chastain is the former head of product development at OpenSea, an online platform for trading non-fungible tokens, or NFTs. He took advantage of his inside knowledge about what tokens would be featured on the OpenSea website to buy and sell those tokens in advance, making about $50,000.

I think there are some serious legal flaws in this case, as I wrote about in this post last summer. I’ll be very interested to see what happens here on appeal.

Attorney Insider Trading

A Brazilian national who was working as a visiting attorney with the U.S. law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP was arrested and charged with insider trading. Romero Cabral Da Costa Neto was arrested last Tuesday. Prosecutors charge that while working at Gibson, Dunn he learned the details about an upcoming merger involving two health care companies, one of which was represented by Gibson, Dunn. He purchased thousands of shares in the target company and made about $40,000 when he sold those shares following the merger. His suspicious trading patterns were identified by the SEC, which has also filed a civil suit against him.

This is any law firm’s nightmare. During their work attorneys frequently come into possession of material, nonpublic information that could improperly be used to profit in the stock market. When they do, they can be treated as corporate insiders for purposes of insider trading law. Law firms typically have detailed policies limiting the ability of their attorneys and employees to trade in stocks, particularly those of firm clients. Neto violated Gibson, Dunn’s policies and accessed confidential firm information about the merger even though he was not working on the deal, and used that information to make his trades.

Gibson, Dunn has fired Neto and is cooperating in the investigation.

The Week Ahead

Monday should be a big day in Trump prosecution world: we have the federal court hearing in Georgia on Mark Meadows’ petition for removal, and the status hearing in the federal case in D.C., where Judge Chutkan should set a trial date.

When I was an AUSA doing appeals (I did about 150 of them over the years), I found that one of the things that the court found most helpful (and professional) was when I would try to give the best and most lucid version of the defendant's argument (which his counsel often failed to do) and then answer it. I was wondering if you could do a version of that here. Specifically, as to the Jan 6 indictment from Jack Smith, I've heard some Trump backers say that there's a good First Amendment defense, pointing out that simply contesting election results is not a crime, and that in order to avoid chilling such contests, the courts should bend over backward not to criminalize even pretty aggressive behavior.

I don't know that I buy that argument, but I don't think the courts will treat it as frivolous. Indeed, I think it's about the best Trump has. So I was wondering if you could outline how that argument would look put in its most erudite and appealing form (which Trump's lawyers are unlikely to do), and then detail how Jack Smith should respond.

I do think this is the aspect of the case that's most likely to draw serious attention from judges, so hearing from an expert (like you) is going to improve my education.

Thanks!

I understand, but if you were a prosecutor trying Chesebro separately, would you spend most of the trial offering evidence of lies about Dominion and Caesar Chavez, tampering with voting machines, slandering election workers, plotting to send phony DOJ letters, late night White House meetings, etc., etc.? The one-sentence cross of most witnesses would be: did Chesebro have anything to do with that? And the answer would be: Never heard of the guy. Is all that evidence even admissible? There’s no hearsay problem, but is proof of activities of which Chesebro was unaware even relevant to whether HE conspired to conduct the affairs of an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity? Does a prosecutor have an inherent right to present evidence of the full scope of the conspiracy a defendant is charged with entering regardless of how much time it takes and how little bearing it has on the defendant’s own guilt? And even if a prosecutor could do that, would it be sensible for her to do it? Wouldn’t cheseboro’s trial tend to become primarily a trial about writing some ridiculous legal memos, and wouldn’t that be very much to his advantage? Can you imagine a joint trial of the two defendants who’ve sought speedy trials so far, Chesebro and Powell? They had a common objective, but there would be very little overlap in the evidence bearing on their activities.